American mutilation of Japanese war dead

During World War II, some members of the United States military mutilated dead Japanese service personnel in the Pacific theater. The mutilation of Japanese service personnel included the taking of body parts as "war souvenirs" and "war trophies". Teeth and skulls were the most commonly taken "trophies", although other body parts were also collected.

The phenomenon of "trophy-taking" was widespread enough that discussion of it featured prominently in magazines and newspapers. Franklin Roosevelt himself was reportedly given a gift of a letter-opener made of a Japanese soldier's arm by U.S. Representative Francis E. Walter in 1944, which Roosevelt later ordered to be returned, calling for its proper burial.[3][4] The news was also widely reported to the Japanese public, where the Americans were portrayed as "deranged, primitive, racist and inhuman". This, compounded by a previous Life magazine picture of a young woman with a skull trophy, was reprinted in the Japanese media and presented as a symbol of American barbarism, causing national shock and outrage.[5][6]

The behavior was officially prohibited by the U.S. military, which issued additional guidance as early as 1942 condemning it specifically.[7] Nonetheless, the behavior was infrequently prosecuted[citation needed] and it continued throughout the war in the Pacific theater, and has resulted in continued discoveries of "trophy skulls" of Japanese combatants in American possession, as well as American and Japanese efforts to repatriate the remains of the Japanese dead.

Trophy-taking

[edit]A number of firsthand accounts, including those of American servicemen, attest to the taking of body parts as "trophies" from the corpses of Imperial Japanese troops in the Pacific Theater during World War II. Historians have attributed the phenomenon to a campaign of dehumanization of the Japanese in the U.S. media, to various racist tropes latent in American society, to the depravity of warfare under desperate circumstances, to the inhuman cruelty of the Imperial Japanese forces, lust for revenge, rage, outrage, or any combination of those factors.[citation needed] The taking of so-called "trophies" was widespread enough that, by September 1942, the Commander in Chief of the Pacific Fleet ordered that "No part of the enemy's body may be used as a souvenir", and any American servicemen violating that principle would face "stern disciplinary action".[8]

Trophy skulls are the most notorious of the souvenirs. Teeth, ears and other such body parts were also taken and were occasionally modified, such as by writing on them or fashioning them into utilities or other artifacts.[9]

Eugene Sledge relates a few instances of fellow marines extracting gold teeth from the Japanese, including one from an enemy soldier who was still alive:

But the Japanese wasn't dead. He had been wounded severely in the back and couldn't move his arms; otherwise he would have resisted to his last breath. The Japanese's mouth glowed with huge gold-crowned teeth, and his captor wanted them. He put the point of his kabar on the base of a tooth and hit the handle with the palm of his hand. Because the Japanese was kicking his feet and thrashing about, the knife point glanced off the tooth and sank deeply into the victim's mouth. The Marine cursed him and with a slash cut his cheeks open to each ear. He put his foot on the sufferer's lower jaw and tried again. Blood poured out of the soldier's mouth. He made a gurgling noise and thrashed wildly. I shouted, "Put the man out of his misery." All I got for an answer was a cussing out. Another Marine ran up, put a bullet in the enemy soldier's brain, and ended his agony. The scavenger grumbled and continued extracting his prizes undisturbed.[10]

U.S. Marine Corps veteran Donald Fall attributed the mutilation of enemy corpses to hatred and desire for vengeance:

On the second day of Guadalcanal we captured a big Jap bivouac with all kinds of beer and supplies ... But they also found a lot of pictures of Marines that had been cut up and mutilated on Wake Island. The next thing you know there are Marines walking around with Jap ears stuck on their belts with safety pins. They issued an order reminding Marines that mutilation was a court-martial offense ... You get into a nasty frame of mind in combat. You see what's been done to you. You'd find a dead Marine that the Japs had booby-trapped. We found dead Japs that were booby-trapped. And they mutilated the dead. We began to get down to their level.[11]

Another example of mutilation was related by Ore Marion, a U.S. marine who suggested that soldiers became "like animals" under harsh conditions:

We learned about savagery from the Japanese ... But those sixteen-to-nineteen-year old kids we had on the Canal were fast learners ... At daybreak, a couple of our kids, bearded, dirty, skinny from hunger, slightly wounded by bayonets, clothes worn and torn, wack off three Jap heads and jam them on poles facing the "Jap side" of the river ... The colonel sees Jap heads on the poles and says, "Jesus men, what are you doing? You're acting like animals." A dirty, stinking young kid says, "That's right Colonel, we are animals. We live like animals, we eat and are treated like animals—what the fuck do you expect?"[11]

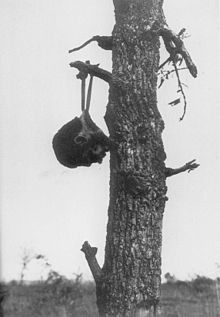

On February 1, 1943, Life magazine published a photograph taken by Ralph Morse during the Guadalcanal campaign showing a severed Japanese head that U.S. marines had propped up below the gun turret of a knocked out Japanese tank. Life received letters of protest from people "in disbelief that American soldiers were capable of such brutality toward the enemy." The editors responded that "war is unpleasant, cruel, and inhuman. And it is more dangerous to forget this than to be shocked by reminders." However, the image of the severed head generated less than half the number of protest letters that an image of a mistreated cat in the very same issue received, suggesting that American backlash was not significant.[12] Years later, Morse recounted that when his platoon came upon the tank with the head mounted on it, the sergeant warned his men not to approach it as it might have been set up by the Japanese in order to lure them in, and he feared that the Japanese might have a mortar tube zeroed in on it. Morse recalled the scene in this way: "'Everybody stay away from there,' the sergeant says, then he turns to me. 'You,' he says, 'go take your picture if you have to, then get out, quick.' So I went over, got my pictures and ran like hell back to where the patrol had stopped."[13]

In October 1943, the U.S. High Command expressed alarm over recent newspaper articles covering American mutilation of the dead. Examples cited included one where a soldier made a string of beads using Japanese teeth and another about a soldier with pictures showing the steps in preparing a skull, involving cooking and scraping of the Japanese heads.[7]

In 1944, the American poet Winfield Townley Scott was working as a reporter in Rhode Island when a sailor displayed his skull trophy in the newspaper office. This led to the poem The U.S. sailor with the Japanese skull, which described one method for preparation of skulls for trophy-taking, in which the head is skinned, towed in a net behind a ship to clean and polish it, and in the end scrubbed with caustic soda.[14]

Charles Lindbergh refers in his diary entries to several instances of mutilations. In the entry for August 14, 1944, he notes a conversation he had with a Marine officer who claimed that he had seen many Japanese corpses with an ear or nose cut off.[7] In the case of the skulls, however, most were not collected from freshly killed Japanese; most came from already partially or fully decayed and skeletonised bodies.[7] Lindbergh also noted in his diary his experiences from an air base in New Guinea, where, according to him, the troops killed the remaining Japanese stragglers "as a sort of hobby" and often used their leg-bones to carve utilities.[9]

Moro Muslim guerillas on Mindanao fought against Japan in World War II. The Moro Muslim Datu Pino sliced the ears off Japanese soldiers and cashed them in with the American guerilla leader Colonel Fertig at the exchange rate of a pair of ears for one bullet and 20 centavos (equivalent to $1.69 in 2023).[15][16][17]

Extent of practice

[edit]According to Weingartner it is not possible to determine the percentage of U.S. troops that collected Japanese body parts, "but it is clear that the practice was not uncommon".[18] According to Harrison only a minority of U.S. troops collected Japanese body parts as trophies, but "their behaviour reflected attitudes which were very widely shared".[7][18] According to Dower, most U.S. combatants in the Pacific did not engage in "souvenir hunting" for body parts.[19] The majority had some knowledge that these practices were occurring, however, and "accepted them as inevitable under the circumstances".[19] The incidents of soldiers collecting Japanese body parts occurred on "a scale large enough to concern the Allied military authorities throughout the conflict and was widely reported and commented on in the American and Japanese wartime press".[20] The degree of acceptance of the practice varied between units. Taking of teeth was generally accepted by enlisted men and also by officers, while acceptance for taking other body parts varied greatly.[7] In the experience of one serviceman turned author, Weinstein, ownership of skulls and teeth were widespread practices.[21]

There is some disagreement between historians over what the more common forms of "trophy hunting" undertaken by U.S. personnel were. John W. Dower states that ears were the most common form of trophy that was taken, and skulls and bones were less commonly collected. In particular he states that "skulls were not popular trophies" as they were difficult to carry and the process for removing the flesh was offensive.[22] This view is supported by Simon Harrison.[7] In contrast, Niall Ferguson states that "boiling the flesh off enemy [Japanese] skulls to make souvenirs was not an uncommon practice. Ears, bones and teeth were also collected".[23] When interviewed by researchers, former servicemen recounted that the practice of taking gold teeth from the dead—and sometimes also from the living—was widespread.[24]

The collection of Japanese body parts began quite early in the campaign, prompting a September 1942 order for disciplinary action against such souvenir taking.[7] Harrison concludes that since the Battle of Guadalcanal was the first real opportunity to take such items, "Clearly, the collection of body parts on a scale large enough to concern the military authorities had started as soon as the first living or dead Japanese bodies were encountered."[7] When Charles Lindbergh passed through customs at Hawaii in 1944, one of the customs declarations he was asked to make was whether or not he was carrying any bones. He was told after expressing some shock at the question that it had become a routine point,[25] because of the large number of souvenir bones discovered in customs, also including "green" (uncured) skulls.[26]

In 1984, Japanese soldiers' remains were repatriated from the Mariana Islands. Roughly 60 percent were missing their skulls.[26] Likewise it has been reported that many of the Japanese remains on Iwo Jima are missing their skulls.[26]

It is possible that the souvenir collection of remains continued into the immediate post-war period.[26]

Context

[edit]According to Simon Harrison, all of the "trophy skulls" from the World War II era in the forensic record in the U.S., attributable to an ethnicity, are of Japanese origin; none come from Europe.[9] A seemingly rare exception to this rule was the case of a German soldier scalped by an American soldier in films shot by the Special Film Project 186[27] near Prague, Czechoslovakia, on May 8, 1945, displaying an M4 Sherman with a skull and bones fixed to it,[28] which was falsely attributed to a Winnebago tribal custom.[29] Skulls from World War II, and also from the Vietnam War, continue turning up in the U.S., sometimes returned by former servicemen or their relatives, or discovered by police. According to Harrison, contrary to the situation in average head-hunting societies, the trophies do not fit in American society. The taking of the objects was socially accepted at the time, but after the war, when the Japanese in time became seen as fully human again, the objects for the most part became seen as unacceptable and unsuitable for display. Therefore, in time they and the practice that had generated them were largely forgotten.[26]

Australian soldiers also mutilated Japanese corpses, most commonly by taking gold teeth from them, despite such acts being officially discouraged by the Australian Army.[30] Such acts were committed by Australian troops most prominently during the Burma and Kokoda Track campaigns.[31] Johnston states that "one could argue that greed rather than hatred was the motive" for this behavior, but "utter contempt for the enemy was also present."[30] Australians are took gold teeth from German corpses during the North Africa campaign, "but the practice was obviously more common in the South-West Pacific."[30] The vast majority of Australian servicemen "clearly found such behaviour abhorrent" but "some of the soldiers who engaged in it were not "hard cases"".[30] According to Johnston, Australian soldiers' "unusually murderous behaviour" towards their Japanese opponents (such as summary executions) was caused by widespread racism, a lack of understanding of Japanese military culture (which also considered the enemy, especially those who surrendered, as unworthy of compassion) and, most significantly, a desire to take revenge against the murder and mutilation of Australian prisoners and native New Guineans during the Battle of Milne Bay and subsequent battles.[32]

Motives

[edit]Dehumanization

[edit]

In the U.S., there was a widely propagated view that the Japanese were subhuman.[33][34] There was also popular anger in the U.S. at the Japanese surprise attack on Pearl Harbor, amplifying pre-war racial prejudices.[23] The U.S. media helped propagate this view of the Japanese, for example describing them as "yellow vermin".[34] In an official U.S. Navy film, Japanese troops were described as "living, snarling rats".[35] The mixture of underlying American racism, which was added to by U.S. wartime propaganda, hatred caused by the Second Sino-Japanese War, and both real and also fabricated Japanese atrocities, led to a general loathing of the Japanese.[34] Although there were objections to the mutilation from among other military jurists, "to many Americans the Japanese adversary was no more than an animal, and abuse of his remains carried with it no moral stigma".[36]

According to Niall Ferguson: "To the historian who has specialized in German history, this is one of the most troubling aspects of the Second World War: the fact that Allied troops often regarded the Japanese in the same way that Germans regarded Russians—as Untermenschen."[37] Since the Japanese were regarded as animals, it is not surprising that Japanese remains were treated in the same way as animal remains.[34]

Simon Harrison comes to the conclusion in his paper, "Skull trophies of the Pacific War: transgressive objects of remembrance", that the minority of U.S. personnel who collected Japanese skulls did so because they came from a society that placed much value in hunting as a symbol of masculinity, combined with a de-humanization of the enemy.[38]

War correspondent Ernie Pyle, on a trip to Saipan after the invasion, claimed that the men who actually fought the Japanese did not subscribe to the wartime propaganda: "Soldiers and Marines have told me stories by the dozen about how tough the Japs are, yet how dumb they are; how illogical and yet how uncannily smart at times; how easy to rout when disorganized, yet how brave ... As far as I can see, our men are no more afraid of the Japs than they are of the Germans. They are afraid of them as a modern soldier is afraid of his foe, but not because they are slippery or rat-like, but simply because they have weapons and fire them like good, tough soldiers."[39]

Brutalization

[edit]Some writers and veterans state that body parts trophy and souvenir taking was a side effect of the brutalizing effects of a harsh campaign.[40]

Harrison argues that, while brutalization could explain part of the mutilations, it does not explain servicemen who, even before shipping off for the Pacific, proclaimed their intention to acquire such objects.[41] According to Harrison, it also does not explain the many cases of servicemen collecting the objects as gifts for people back home.[41] Harrison concludes that there is no evidence that the average serviceman collecting this type of souvenirs was suffering from "combat fatigue". They were normal men who felt that was what their loved ones wanted them to collect for them.[4] Skulls were sometimes also collected as souvenirs by non-combat personnel.[40]

A young Marine recruit, who had arrived on Saipan with his buddy Al in 1944, after the island was secure, provides an eyewitness account. After a brief firefight the night before, he and a small group of other marines find the body of a straggler who had apparently shot himself:

I would have guessed that the dead Japanese was only about fourteen years old and there he lay dead. My thoughts turned to some mother back in Japan who would receive word that her son had been killed in battle. Then one of the Marines, who I found out later had been through other campaigns, reached over and roughly grabbed the Japanese soldier by the belt and ripped his shirt off. Somebody said, 'What are you looking for?' And he said, 'I'm looking for a money belt. Japs always carry money belts.' Well, this Jap didn't. Another Marine veteran of combat saw that the dead soldier had some gold teeth, so he took the butt of his rifle and banged him on the jaw, hoping to extract the gold teeth. Whether he did or not I don't know, because at that point I turned around and walked away. I went over to where I thought no one would see me and sat down. Although my eyes were dry, inside my heart was wrenching, not at seeing the dead soldier, but at seeing the way some of my comrades had treated that dead body. That bothered me a great deal. Pretty soon Al came over and sat down beside me and put his arm around my shoulder. He knew what I was feeling. When I turned to look at Al he had tears running down his face.[42]

Revenge

[edit]

Bergerud writes that U.S. troops' hostility towards their Japanese opponents largely arose from incidents in which Japanese soldiers committed war crimes against Americans, such as the Bataan Death March and other incidents conducted by individual soldiers. For instance, Bergerud states that the U.S. Marines on Guadalcanal were aware that the Japanese had beheaded some of the Marines captured on Wake Island prior to the start of the campaign. However, that type of knowledge did not necessarily lead to revenge mutilations. One Marine states that they falsely thought the Japanese had not taken any prisoners of war at Wake Island and so as revenge, they killed all Japanese that tried to surrender.[43][44]

According to one Marine, the earliest account of U.S. troops wearing ears from Japanese corpses took place on the second day of the Guadalcanal Campaign in August 1942 and occurred after photos of the mutilated bodies of Marines on Wake Island were found in Japanese engineers' personal effects. The account of the same Marine also states that Japanese troops booby-trapped some of their own dead as well as some dead Marines and also mutilated corpses; the effect on Marines being "We began to get down to their level".[11] According to Bradley A. Thayer, referring to Bergerud and interviews conducted by Bergerud, the behaviors of American and Australian soldiers were affected by "intense fear, coupled with a powerful lust for revenge".[45]

Weingartner writes, however, that U.S. Marines were intent on taking gold teeth and making keepsakes of Japanese ears already while they were en route to Guadalcanal.[46]

Souvenirs and bartering

[edit]Factors relevant to the collection of body parts were their economic value, the desire both of the "folks back home" for a souvenir and of the servicemen themselves to have a keepsake when they returned home.

Some of the collected souvenir bones were modified: turned into letter-openers, and may be an extension of trench art.[9]

Pictures showing the "cooking and scraping" of Japanese heads may have formed part of the large set of Guadalcanal photographs sold to sailors which were circulating on the U.S. West-coast.[47] According to Paul Fussell, pictures showing this type of activity, i.e. boiling human heads, "were taken (and preserved for a lifetime) because the Marines were proud of their success".[14]

According to Weingartner, some of the U.S. marines who were about to take part in the Guadalcanal Campaign were looking forward to collecting Japanese gold teeth for necklaces and to preserving Japanese ears as souvenirs.[18]

In many cases (and unexplainable by battlefield conditions) the collected body parts were not for the use of the collector but instead meant to be gifts to family and friends at home,[41] in some cases as the result of specific requests from home.[41] Newspapers reported of cases such as a mother requesting permission for her son to send her an ear or a bribed chaplain that was promised by an underage youth "the third pair of ears he collected."[41]

Another example of that type of press is Yank, which, in early 1943, published a cartoon showing the parents of a soldier receiving a pair of ears from their son.[47] In 1942, Alan Lomax recorded a blues song where a soldier promises to send his child a Japanese skull, and a tooth.[41] Harrison also makes note of the Congressman that gave President Roosevelt a letter-opener carved out of bone as examples of the social range of these attitudes.[4]

Trade sometimes occurred with the items, such as "members of the Naval Construction Battalions stationed on Guadalcanal selling Japanese skulls to merchant seamen" as reported in an Allied intelligence report from early 1944.[40] Sometimes teeth (particularly the less common gold teeth) were also seen as a tradable commodity.[40]

U.S. reaction

[edit]"Stern disciplinary action" against human remains souvenir taking was ordered by the Commander-in-Chief of the Pacific Fleet as early as September 1942.[7] In October 1943 General George C. Marshall radioed General Douglas MacArthur about "his concern over current reports of atrocities committed by American soldiers".[48] In January 1944 the Joint Chiefs of Staff issued a directive against the taking of Japanese body parts.[48] Simon Harrison writes that directives of this type may have been effective in some areas, "but they seem to have been implemented only partially and unevenly by local commanders".[7]

On May 22, 1944, Life magazine published a photo[49] of an American girl with a Japanese skull sent to her by her naval officer boyfriend. The image caption stated: "When he said goodbye two years ago to Natalie Nickerson, 20, a war worker of Phoenix, Ariz., a big, handsome Navy lieutenant promised her a Jap. Last week Natalie received a human skull, autographed by her lieutenant and 13 friends, and inscribed: "This is a good Jap – a dead one picked up on the New Guinea beach." Natalie, surprised at the gift, named it Tojo. The letters Life received from its readers in response to this photo were "overwhelmingly condemnatory"[50] and the Army directed its Bureau of Public Relations to inform U.S. publishers that "the publication of such stories would be likely to encourage the enemy to take reprisals against American dead and prisoners of war".[51] The junior officer who had sent the skull was also traced and officially reprimanded.[4] This was, however, done reluctantly, and the punishment was not severe.[52]

The image was widely reprinted in Japan as anti-American propaganda.[53]

The Life photo also led to the U.S. military taking further action against the mutilation of Japanese corpses. In a memorandum dated June 13, 1944, the Army JAG asserted that "such atrocious and brutal policies" in addition to being repugnant also were violations of the laws of war, and recommended the distribution to all commanders of a directive pointing out that "the maltreatment of enemy war dead was a blatant violation of the 1929 Geneva Convention on the Sick and Wounded, which provided that: After each engagement, the occupant of the field of battle shall take measures to search for the wounded and dead, and to protect them against pillage and maltreatment." Such practices were also in violation of the unwritten customary rules of land warfare and could lead to the death penalty.[54] The Navy JAG mirrored that opinion one week later, and also added that "the atrocious conduct of which some U.S. servicemen were guilty could lead to retaliation by the Japanese which would be justified under international law".[54]

On June 13, 1944, the press reported that President Roosevelt had been presented with a letter-opener made out of a Japanese soldier's arm bone by Francis E. Walter, a Democratic congressman.[4] Supposedly, the president commented, "This is the sort of gift I like to get", and "There'll be plenty more such gifts".[55] Several weeks later it was reported that it had been given back with the explanation that the President did not want this type of object and recommended it be buried instead. In doing so, Roosevelt was acting in response to the concerns which had been expressed by the military authorities and some of the civilian population, including church leaders.[4]

In October 1944, the Right Rev. Henry St. George Tucker, the Presiding Bishop of the Episcopal Church in the United States of America, issued a statement which deplored "'isolated acts of desecration with respect to the bodies of slain Japanese soldiers and appealed to American soldiers as a group to discourage such actions on the part of individuals".[56][57]

Japanese reaction

[edit]News that President Roosevelt had been given a bone letter-opener by a congressman was widely reported in Japan. The Americans were portrayed as "deranged, primitive, racist and inhuman". That reporting was compounded by the previous May 22, 1944, Life magazine picture of the week publication of a young woman with a skull trophy, which was reprinted in the Japanese media and presented as a symbol of American barbarism, causing national shock and outrage.[5][6] Military history writer Edwin P. Hoyt argues that two U.S. media reports of Japanese skulls and bones being sent back to the U.S. were exploited very effectively by Japanese propaganda. These actions contrasted starkly with the Shinto religion's emphasis on respectful treatment of human remains. This aspect of Shinto, combined with the propaganda spotlight on American atrocities, contributed directly to the mass suicides on Saipan and Okinawa after the Allied landings.[5][58] According to Hoyt, "The thought of a Japanese soldier's skull becoming an American ashtray was as horrifying in Tokyo as the thought of an American prisoner used for bayonet practice was in New York."[59]

See also

[edit]- Debate over the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki

- Headhunting

- Jap hunts

- Rape during the occupation of Japan

- Statism in Shōwa Japan

- Scalping

- Japanese war crimes

References

[edit]- ^ Roeder, George H. Jr. (Fall 1995). "Missing on the home front". National Forum. Archived from the original on October 18, 2016.

- ^ Lewis A. Erenberg; Susan E. Hirsch (1996). The War in American Culture: Society and Consciousness During World War II. University of Chicago Press. p. 52. ISBN 978-0226215112.

- ^ Weingartner 1992, p. 65.

- ^ a b c d e f Harrison 2006, p. 825.

- ^ a b c Harrison 2006, p. 833.

- ^ a b Dickey, Colin (2012). Afterlives of the Saints: Stories from the Ends of Faith. Unbridled Books. ISBN 978-1609530723.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Harrison 2006, p. 827.

- ^ Paul Fussell. Wartime: Understanding and Behavior in the Second World War. 1990, page 117

- ^ a b c d Harrison 2006, p. 826.

- ^ (With the Old Breed: At Peleliu and Okinawa. p. 120

- ^ a b c Thayer 2004, p. 186.

- ^ "War, Journalism, and Propaganda"

- ^ Ben Cosgrove (February 19, 2014). "Guadalcanal: Rare and Classic Photos From a Pivotal WWII Campaign". Time. Archived from the original on November 14, 2014. Retrieved October 17, 2016.

- ^ a b Harrison 2006, p. 822.

- ^ Keats, John (1990). They Fought Alone. Time-Life. p. 285. ISBN 978-0809485543.

- ^ McClintock, Michael (1992). Instruments of Statecraft: U.S. Guerrilla Warfare, Counterinsurgency, and Counter-terrorism, 1940–1990. Pantheon Books. p. 93. ISBN 978-0394559452.

- ^ Tucci, Frank (2009). The Old Muslim's Opinions: A Year of Filipino Newspaper Columns. iUniverse. p. 130. ISBN 978-1440183423.

- ^ a b c Weingartner 1992, p. 56.

- ^ a b Dower 1986, p. 66.

- ^ Harrison 2006, p. 818.

- ^ Harrison 2006, pp. 822, 823.

- ^ Dower 1986, p. 65.

- ^ a b Ferguson 2007, p. 546.

- ^ Film exposes Allies' Pacific war atrocities Horrific footage shot during battle with Japanese shows execution of wounded and bayoneting of corpses. Jason Burke The Observer, Sunday June 3, 2001

- ^ Dower 1986, p. 71.

- ^ a b c d e Harrison 2006, p. 828.

- ^ Chasing Hitler YouTube

- ^ "Liberated Czechoslovakia; Wounded and Dead Germans; POWS". Steven Spielberg Film and Video Archive. Retrieved October 17, 2016.

- ^ The Taking and Displaying of Human Body Parts As Trophies by Amerindians. Chacon and Dye, p. 625 ISBN 978-0387483030

- ^ a b c d Johnston 2000, p. 82.

- ^ T. R. Moreman "The jungle, the Japanese and the British Commonwealth armies at war, 1941–45", p. 205

- ^ Johnston 2000, pp. 81–100.

- ^ Weingartner 1992, p. 67.

- ^ a b c d Weingartner 1992, p. 54.

- ^ Weingartner 1992, p. 54 Japanese were alternatively described and depicted as "mad dogs", "yellow vermin", termites, apes, monkeys, insects, reptiles and bats etc.

- ^ Weingartner 1992, pp. 66, 67.

- ^ Ferguson 2007, p. 182.

- ^ Harrison 2006.

- ^ Ernie Pyle (February 26, 1945). "The Illogical Japs". Rocky Mountain News. Retrieved October 17, 2016 – via Indiana University.

- ^ a b c d Harrison 2006, p. 823.

- ^ a b c d e f Harrison 2006, p. 824.

- ^ Bruce Petty, Saipan: Oral Histories of the Pacific War, McFarland & Company, Inc., 2002, ISBN 0786409916, p. 119

- ^ Stanley Coleman Jersey "Hell's islands: the untold story of Guadalcanal", p. 169, 170

- ^ See also: Allied war crimes during World War II#Asia and the Pacific War

- ^ Thayer 2004, p. 185.

- ^ Weingartner 1992, p. 556.

- ^ a b Weingartner 1992, pp. 56, 57.

- ^ a b Weingartner 1992, p. 57.

- ^ "Picture of the Week". Life. Time Inc. May 22, 1944. p. 35. ISSN 0024-3019. Retrieved August 8, 2010.

- ^ Weingartner 1992, p. 58.

- ^ Weingartner 1992, p. 60.

- ^ Weingartner 1992, pp. 65, 66.

- ^ Curley, John J. (2012). "Bad Manners: A 1944 Life Magazine "Picture of the Week"". Visual Resources. 28 (3): 240–262. doi:10.1080/01973762.2012.702659. S2CID 194083703.

- ^ a b Weingartner 1992, p. 59.

- ^ Drew Pearson (June 13, 1944). "Jones-Clayton Forces Behind Texas Revolt". The Washington Merry-Go-Round. The Nevada Daily Mail.

- ^ "Tucker Deplores Desecration of Foe; Mutilation of Japanese Bodies Contrary to Spirit of Army, He Says of 'Isolated' Cases". The New York Times. October 14, 1944.

- ^ "The Morals of Victory". Time. October 23, 1944. Archived from the original on October 24, 2012. Retrieved May 11, 2008.

- ^ Hoyt (1987), pp. 357–361

- ^ Hoyt (1987), pp. 358

Sources

[edit]- Weingartner, James J. (February 1992). "Trophies of War: U.S. Troops and the Mutilation of Japanese War Dead, 1941–1945". Pacific Historical Review. 61 (1): 53–67. doi:10.2307/3640788. JSTOR 3640788. Archived from the original on August 11, 2011. Retrieved August 11, 2011.

U.S. Marines on their way to Guadalcanal relished the prospect of making necklaces of Japanese gold teeth and 'pickling' Japanese ears as keepsakes.

- Harrison, Simon (2006). "Skull Trophies of the Pacific War: transgressive objects of remembrance". Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute. 12 (4): 817–836. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9655.2006.00365.x. Archived from the original on March 8, 2021. Retrieved October 17, 2016.

- Thayer, Bradley A. (2004). Darwin and international relations: on the evolutionary origins of war and ethnic conflict. University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 978-0813123219. Retrieved January 24, 2011.

- Johnston, Mark (2000). Fighting the Enemy. Australian Soldiers and their Adversaries in World War II. Melbourne: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521782228. Retrieved January 24, 2011.

- Dower, John W. (1986). War Without Mercy. Race and Power in the Pacific War. London: Faber and Faber. pp. 64–66. ISBN 0571146058. Retrieved January 24, 2011.

- Ferguson, Niall (2007). The War of the World. History's Age of Hatred. London: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0141013824. Retrieved January 24, 2011.

Further reading

[edit]- Paul Fussell, "Wartime: Understanding and Behavior in the Second World War" ISBN 978-0195065770

- Bourke, Joanna (November 27, 2000). An Intimate History of Killing. Basic Books. pp. 37–43. ISBN 978-0465007387.

- Fussell, "Thank God for the Atom Bomb and other essays" (pages 45–52) ISBN 978-0786103959

- Aldrich, "The Faraway War: Personal diaries of the Second World War in Asia and the Pacific" ISBN 978-0385606790

- Hoyt, Edwin P. (1987). Japan's War: The Great Pacific Conflict. London: Arrow Books. ISBN 0099635003.

- Charles A. Lindbergh (1970). The Wartime Journals of Charles A. Lindbergh. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, Inc. ISBN 0151946256.

External links

[edit]- One War Is Enough War Correspondent EDGAR L. JONES 1946

- Fenton, Ben (August 6, 2005). "American troops 'murdered Japanese PoWs'". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on January 14, 2013. Retrieved July 14, 2021.

- The US Sailor with the Japanese Skull by Winfield Townley Scott

- Boorstein, Michelle (July 3, 2007). "Eerie Souvenirs From the Vietnam War". The Washington Post.

- 2002 Virginia Festival of the Book: Trophy Skulls

- Weingartner, James (Spring 1996). "War against Subhumans: Comparisons between the German War against the Soviet Union and the American War against Japan, 1941–1945". The Historian. 58 (3). Taylor & Francis Ltd: 557–573. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6563.1996.tb00964.x. JSTOR 24449433.

- Brcak, Nancy; Pavia, John R. (Summer 1994). "Racism in Japanese and U.S. Wartime Propaganda". The Historian. 56 (4). Taylor & Francis Ltd: 671–684. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6563.1994.tb00926.x. JSTOR 24449072.

- "Macabre Mystery: Coroner tries to find origin of skull found during raid by deputies". The Pueblo Chieftain.

- Allen, David (May 13, 2004). "Skull from WWII casualty to be buried in grave for Japanese unknown soldiers". Stars and Stripes. Retrieved July 14, 2021.

- HNET review of Peter Schrijvers. The GI War against Japan: American Soldiers in Asia and the Pacific during World War II.

- "A Japanese soldier's skull is propped up on a burned-out Jap tank by U.S. troops. Fire destroyed the rest of the corpse". Life. February 1, 1943. p. 27.

- The May 1944 Life magazine picture of the week (image)